Set in East Texas in 1999, Sound of Hope: The Story of Possum Trot shows how spiritual values helped persuade the people in a rural community to adopt 77 children languishing in the state foster system. Based on a true story, the movie tells its story with a compelling sense of honesty and realism.

Reverend W.C. Martin (Demetrius Gross) leads the Bennett Missionary Baptist church, a small but devoted parish, helped by his wife Donna (Nika King) and other congregants. At home the Martins struggle with bills while raising their children Ladonna (Kaysi J. Bradley) and Princeton (Taj Johnson).

The loss of her mother Murtha (Della Golden), who raised 18 children, brings Donna to the realization that she wants to adopt a child. W.C. worries they can’t afford the additional expenses, but Donna goes ahead after meeting Susan Ramsey (Elizabeth Mitchell), a liaison with the foster system.

The script by Joshua Weigel (who also directed) and Rebekah Weigel at times shifts to separate story lines. One involves Terri (Diaana Babnicova), a troubled orphan who has isolated herself in a dream world. Another follows young Mercedes (Aria Pulliam) and Tyler (Asher Clay), siblings who have been abused by their mother.

Over W.C.’s misgivings, Donna brings Mercedes and Tyler into her home. The experience, while not without problems, is so enriching that W.C. convinces his congregation that they should adopt as well. W.C. insists to Susan that he wants to take the foster system’s most difficult cases.

One of those is Terri, who disrupts the Martin family when she arrives. She throws tantrums, steals from her sister, and sneaks out of the house. Sessions with a therapist don’t seem to help. As incidents escalate, Donna finds herself questioning both her husband and her faith.

As director, Joshua Weigel takes a low-key approach to the story. Scenes are staged simply, but with respect for the characters and with honesty about their events. The subplots aren’t always crucial to the movie’s main messages, and supporting characters can sometimes feel shortchanged, shoehorned into a story that’s really about something else.

However, the heart of the movie — the conflicts between W.C. and his wife, between Terri and her new parents, between Susan and foster parents — feel genuine, not artificially pumped up. Moments of catharsis and bonding are similarly understated (apart from Sean Johnson’s occasionally pointed score).

The movie’s lessons may seem too obvious at times, but they are delivered with a disarming sincerity. The performances in particular help lift Sound of Hope up from mere preaching. Demetrius Gross is excellent as Reverend Martin, a strong, domineering presence who is still capable of sensitivity. Nika King as his wife Donna has the most demanding role, called upon to be jubilant or dismayed or bewildered about her children’s behavior.

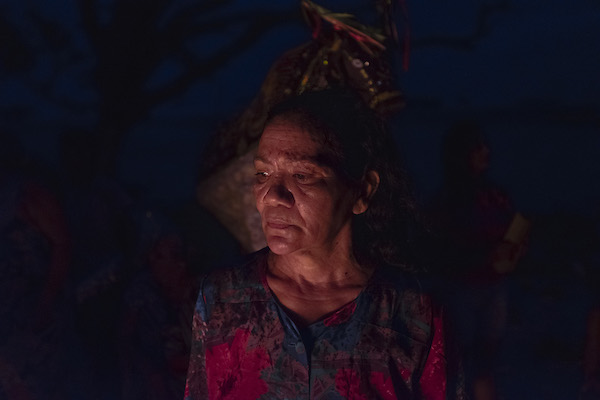

Diaana Babnicova may be the real find here. Nothing in the script phases her, whether she’s asked to explode in a screaming rage or confront doubts about her sanity. Babnicova gives in to the role without judging Terri, earning viewers’ sympathy the hard way, without asking for it.

This is the latest release from Angel Studios, the Utah-based company that released the controversial Sound of Freedom and the unexpectedly solid biopic Cabrini. In addition, Angel partnered with The Daily Wire (co-founded by Ben Shapiro) to distribute the movie theatrically. That move caused executive producer Letitia Wright to announce that she has no affiliation with The Daily Wire.

It’s a shame that there’s even a hint of political controversy attached to Sound of Hope. This is a film that tries to take a positive approach to a stirring human interest story, neither exploiting its characters nor preaching to its audience.

Credits: Directed by: Joshua Weigel. Written by Joshua Weigel and Rebekah Weigel. Produced by Joshua Weigel and Rebekah Weigel, p.g.a. Executive producers: Letitia Wright, Joe Knittig, Nika King. Directors of photography: Benji Bakshi, Sean Patrick Kirby. Production designer: Debbi DeVilla. Editor: David Andalman. Music by Sean Johnson. Cast: Nika King, Demetrius Grosse, Elizabeth Mitchell, Diaana Babnicova, Elizabeth Mitchell, Kaysi J. Bradley, Taj Johnson, Della Golden.

Top: Demetrius Grosse, Diaana Babnicova, Nika King. Center: Nika King. Bottom: Diaana Babnicova. Photos courtesy Peachtree Productions.