In Little Richard: I Am Everything, Richard Penniman says, “I’m the emancipator, the architect. I’m the one that started it all.” But director Lisa Cortés has a more ambitious agenda. For her, Little Richard is rock’s ultimate victim.

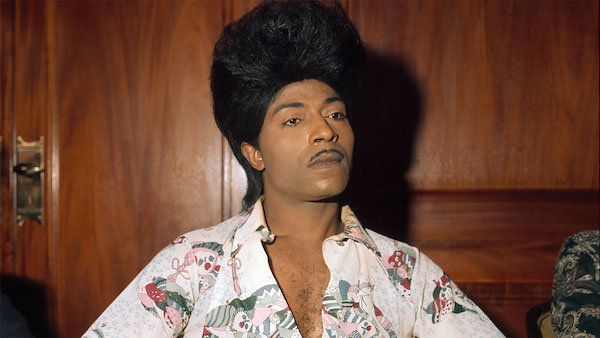

A self-professed gay black performer from Macon, Georgia, Penniman forged a career in medicine shows, on the chitlin’ circuit, and in nightclubs, occasionally performing in drag. He borrowed liberally from artists like Billy Wright and Esquerita, fashioning himself as a pompadoured singer and pianist sporting flamboyant costumes. His musical influences included Louis Prima, Ike Turner, Sister Rosette Tharpe, and New Orleans shouters and belters.

Penniman combined blues, gospel and pop in ways similar to Fats Domino, Huey Smith, and any number of other performers—only outsized. He would clamber atop pianos, strip, push his audiences into frenzies.

Unfortunately, Penniman lived in a highly segregated society where homosexuality was outlawed. Even so, after signing with Specialty Records, he had a string of indelible hits. Like many performers of the time, he was not fully compensated for his work. White artists like Elvis Presley and, notoriously, Pat Boone covered his songs; later, he was a huge influence on The Beatles (who opened for him during a tour of England) and The Rolling Stones.

Unfortunately for this documentary, most of Penniman’s visual record comes after his prime. He appeared in a few movies, notably The Girl Can’t Help It. In those he routinely lip-synched to recorded tracks.

By the mid-sixties, he was considered an oldies act. This was true for most of his contemporaries like Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins. Elvis become a movie star, Jerry Lee Lewis switched to country music, and the rock industry on the whole was littered with has-beens. Like Berry, who never regained his early commercial success, Penniman spent fruitless years trying to re-establish himself, alternately abandoning his past and embracing it again.

It’s a sad story that is almost a template for rock careers. Very few performers can sustain careers for decades. Everyone falls out of favor at some point, and not everyone can claw back.

Cortés positions Penniman as a victim of society incapable of accepting him as a star. She buttresses her film with a string of historians, ethnomusicologists, and activists who use words like “non-normative.” The documentary tries to demystify Little Richard by dragging him into academia, by pigeonholing his sexuality, by shrinking his achievements and explaining away his magic.

Worst of all, people talk over his music. Not one song is heard in its entirety until the closing credits.

Penniman still bursts through the documentary’s portrait of him, smashing the frames confining him with exuberant verbal riffs and explosive songs. (And let’s note: European television handled rock music much better than the US.) Perhaps Little Richard: I Am Everything will convince viewers to seek out Penniman’s music rather than dwell on his problems.

Little Richard: I Am Everything is an official selection of the U.S. Documentary Competition at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival. Photos courtesy of Sundance Institute.