In a Hong Kong cinema known for action heroes and comedians, Anthony Wong is an anomaly. A classically trained actor, he started out in movies playing villains before branching out into a wide array of roles: policeman, music producer, martial arts instructor, assassin, demon, shopkeeper, and, in his latest feature Still Human, paraplegic.

What sets Wong apart from his colleagues is the empathy he has for his characters. He burrows deeply into roles, finding connections to people we often avoid in real life. In Dante Lam’s Beast Cops, Wong hurls himself through a grim Hong Kong underworld to extricate himself from blackmail. In the coming-of-age romance Just One Look, his small-time triad boss struggles between saving face and admitting remorse for his crimes. In Johnnie To’s The Mission, Wong’s hit man tries to play by obsolete rules, holding himself to standards that no longer apply. In each case, the actor finds ways to make his characters real and believable for viewers. Even when violence escalates out of control, his characters’ actions carry an unassailable logic.

Over the past five decades, Wong has worked with every significant Hong Kong director, from John Woo and Tsui Hark to Sylvia Chang and newcomer Oliver Siu-kuen Chan. Filmmakers have learned that Wong always commits himself fully to his performances, whether in comedies, fantasies, cop thrillers, or family dramas.

Wong attended the recent Far East Film Festival in Udine, where he received a Golden Mulberry Award for Outstanding Achievement, a testament to his body of work. He was a guest of the first edition of the festival in 1999, which screened Beast Cops. This year the festival showed his film debut, My Name Ain’t Suzie (1985, directed by Angie Chen), and his latest, Still Human (2018, directed by Oliver Siu-kuen Chan).

Wong won Best Actor at the 39th Hong Kong Film Awards for his role in Still Human; the movie also won Best New Director (Chan) and Best New Performer (Crisel Consunji).

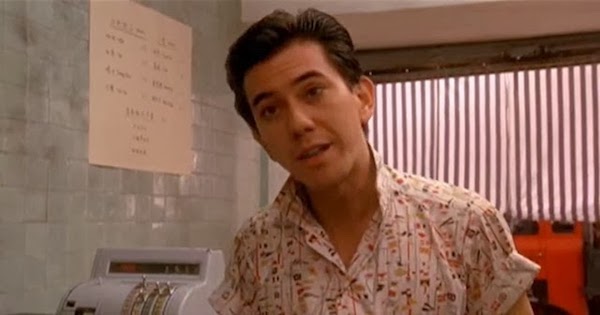

The actor spoke the afternoon before accepting his Outstanding Achievement award at Udine. He started by providing background to his feature debut, where he played Jimmy Koch, a mixed-race petty crook who will betray at least two of his lovers.

“I saw an advertisement for the part in a newspaper,” he said. “I didn’t know how to contact anybody, so I spoke to my friend [director] Herman Yau, who got me a name for the audition. I went and saw a lot of male models trying for the part. I felt very humble, scared a little bit, because I’m not typically handsome. I thought maybe my acting will win them over. After the audition, I waited for a long, long time. It turned out the bosses wanted another actor. Director Angie Chen was the only one who wanted me.”

Interviewed separately, Angie Chen remembered casting Wong because “I believed in him. He didn’t consciously try to act, he just played himself. And that made the movie. There was all this anger, this angst in him that all came out, very naturally, without pretense.”

Wong pointed out the similarities between his role and his real life. “Jimmy is an abandoned child born of an American sailor. He grew up in the Wan Chai area, a kind of red-light district where the film is set. In real life, I also grew up in Wan Chai, and I was also looking for my father, who was English. And just like the movie, last year, after so much time, I finally reconnected with my family. They live in Australia now. I saw the grave where my father was buried.”

After completing the film, Wong entered the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. “I realized I knew nothing about acting,” he said. “When I watched the film a few years later, I saw why Angie chose me for this role: because I didn’t know how to act. If I’m going to play this role again today, I wouldn’t be able to do it right.”

Wong returned to movies in genre roles: Stephen Chow comedies, Category III sex and horror outings. He had more substantial parts in John Woo’s Hard Boiled and Ringo Lam’s Full Contact. Often he was the most memorable performer in otherwise forgettable films.

“I did a lot of crappy movies,” he admitted. “I can’t remember everything I’ve done.” At the time Wong felt typecast because of his race; later he accepted roles to help pay for his mother’s medical bills.

Wong began to display more depth and nuance in his collaborations with Johnnie To. Films like The Mission, Exiled, and Vengeance show Wong’s professional killer as conflicted, even remorseful about his past. At the same time, Wong was fearless in genre releases that explored bisexuality, cannibalism and necrophilia.

His role as a police inspector in Infernal Affairs was a revelation. (Martin Sheen played the corresponding part in The Departed, Martin Scorsese’s version of the story.) Surrounded by corruption and chaos, Wong exerted his authority in a quiet, dignified manner.

“My uncle was a policeman,” he said. “Normally when I watch people act as policemen, they try to be very powerful, authoritative. I played it a different way. I played him as a banker, not a policeman. It’s only a job. I go to the office, I do the job, and then I go home.”

Wong consistently downplays his work, saying of his role as a music promoter in 20 30 40, “I only remember the wig.” It’s actually an astute, finely calibrated performance, one that makes clear the promoter’s moral qualms as he tries to convince two naive and untalented girls that he can make them stars.

The actor, who speaks excellent English, has worked on a few foreign productions, like the 2006 version of The Painted Veil with Edward Norton and Naomi Watts and The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor. Of Jackie Chan’s The Medallion, he remembered “waiting a lot (of time). Waiting a whole week, for example. When they didn’t call me onto the set, I would swim.”

Wong also costarred with John Simm in the eight-episode ITV series Strangers (2018). The story line follows a British professor who learns that his wife had another family in Hong Kong, where Wong is an ex-cop with questions about her death. “Almost all the time in Strangers I followed the director [Paul Andrew Williams]. He had a really strong point of view. You can’t argue with him, just follow him. Just make it easy.”

Wong has studied kung fu throughout his career, but rarely appeared in traditional martial arts films. One exception was Ip Man: The Final Fight (2013), where he offered a subdued, thoroughly convincing version of the wing chun teacher whose most famous student was Bruce Lee.

“My kung fu helped me nothing in Ip Man,” he laughed. “Wing chun is a completely different style. I had to learn from the very beginning, start all over with wing chun. Kung fu is good for you, but I didn’t study it to help my career. One way it did help? Move faster. When they are about to set off an explosion, three, two, one, I can jump before they get to one.”

Wong brought up the heyday of Hong Kong cinema, acknowledging plenty of slapdash releases at the time but pointing out that the industry used to release some 300 features a year. “Nowadays Hong Kong makes about 50 movies a year, and out of those, maybe 20 are made by newcomers. Despite all the obstacles, there is a group of young filmmakers tackling topics they are passionate about. Not necessarily political topics, but something they want to tell in stories. I find that admirable.”

The actor’s latest project, Still Human, came about through the industry’s film development efforts. First-time director Oliver Siu-kuen Chan won a three million HK dollar grant from the First Feature Film Initiative for her screenplay, and was mentored through production by executive producer Fruit Chan. Wong joked that he took the lead without pay because “she could not afford me. In fact I told the funding organizations that you can’t make a good movie for three million HK dollars. They’ve since raised it to five million.”

Still Human is a character study of Leung, played by Wong, a construction worker paralyzed in a worksite accident. Confined to a wheelchair in a public housing apartment, he is dependent on caregivers, but so demanding that few remain with him for long. A friend persuades him to hire Evelyn Santos, a Filipina immigrant (played by Crisel Consunji).

“The Hong Kong film industry has been missing stories with ethnic characters from the Philippines or India,” Wong said. “The main reason why I agreed to do the script is because it’s about an immigrant, and it’s not portraying the culture negatively.”

In a wheelchair or bed for almost all of Still Human, Wong joked that his part wasn’t demanding. “It’s very easy to sit there not moving. We say it’s ‘using your head to act.’ Or we call it British-style acting.”

In reality, Wong built a meticulous portrait that captures his character’s physical limitations, including details that movies often overlook. Like how difficult it is for Leung to use his hands.

“The hands, how his fingers were curled up, that was in the original script,” Wong said. “At the beginning I refused to do that, it’s so inconvenient. But when I remembered my mom, I said yes, I have to do it that way, because it’s real.”

The actor cared for his mother, who was also confined to a wheelchair, for the last ten years of her life. “So I was already familiar with the situation, with that kind of character and behavior.”

Asked how much of his performances are based on his experiences, and how much on his observations, Wong replied, “It’s probably half and half. When you create a character, part of that character is you, has to be you. To take an example, how do you play Hamlet? You use yourself to do it, you put yourself, your experiences, and your feeling into the character. And then you use the script, the director, what he or she wants. When we go onto the set, just tell me what want. What do you want me to say?”

But in his best work, Wong reaches beyond the script. His Leung has moments of frustration, despair, bitterness that stem from personal feelings quite apart from whatever direction he received.

“That’s called emotional transference,” Wong said. “That character is in a state of hopelessness. For me, my career, having been blacklisted for five years, when I act I use this emotional transference for Leung. Although our basic situations aren’t the same, my career and my life feel quite similar to Leung’s. So I can use the same feelings.”

During the 2014 “umbrella movement” in Hong Kong, Wong spoke out for democracy and human rights. Since then he has been unable to find work on Mainland Chinese productions. Typically, he joked about what happened to him.

“Five years ago there was a mix-up between me and the activist Anthony Wong. There are two Wongs, and he was on the blacklist. I was told I wasn’t on the list, but I’m still banned from working. Actually, I don’t know what is happening. People say they can help me, but then later they tell me it’s hopeless. All I know is that all my jobs have been banned.”

Wong has been working steadily in theater. He co-founded the Dionysus Contemporary Theatre in 2013, and will next be appearing in a Cantonese adaptation of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart. Despite building a loyal fan base with midnight movies like The Untold Story and The Sleep Curse, Wong has abandoned the horror genre.

“Mostly because of aging,” he said. “When someone, me, anyone, when we are young, there is a kind of anger, power in the heart. When you grow up, in my case at least, and depending on the government, there’s nothing left of that anger inside. I don’t want to do horror anymore. Instead I want to remake every single role Andy Lau has played in movies.”

Wong pointed to Johnnie To’s Exiled as one of his favorite roles, but also cited Still Human. “I really like this one,” he said. “If they made it in the old days, Crisel’s character would be cast with a very famous actress, and her skin would be colored darker to become a Filipino maid. Most likely I would not be cast. Maybe they would cast Andy Lau. In the end, the Crisel character would marry the paraplegic in the wheelchair, and then he would stand up.”