Understated account of an elderly drug runner for the Mexican cartels. Director and star Clint Eastwood remains one of America’s most talented, and subversive, filmmakers.

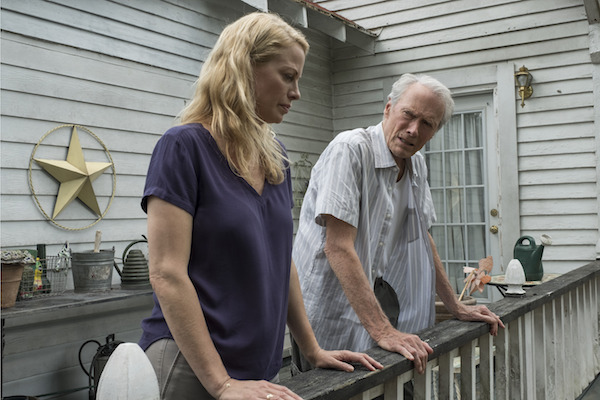

The first shots of Clint Eastwood in The Mule are shocking. Since his last big-screen appearance in Trouble with the Curve, he has diminished physically. His voice is weak and raspy, his gait tentative, his reactions slow. Even if he is acting his frailty, Eastwood can’t hide his age.

The first shots of Clint Eastwood in The Mule are shocking. Since his last big-screen appearance in Trouble with the Curve, he has diminished physically. His voice is weak and raspy, his gait tentative, his reactions slow. Even if he is acting his frailty, Eastwood can’t hide his age.

Earl Stone, his character in The Mule, is the last person you’d expect to be mixed up with a Mexican drug cartel. And that’s about the whole narrative to Nick Schenck’s screenplay (based on a New York Times Magazine article by Sam Dolnick). It doesn’t matter how modest on its surface The Mule is. In its unassuming way, the movie reveals a lot about how we live.

Like many of us, Earl has been made obsolete. He worked for decades at a career in horticulture (sacrificing his family in the process), only to be undone by bad choices and by the Internet. When he loses his Peoria business and home, he has nowhere to turn.

His daughter Iris (Alison Eastwood) hasn’t spoken to him since he failed to show up at her wedding. His ex-wife Mary (Dianne Wiest) can’t contain her anger and hurt. One granddaughter, Ginny (Taissa Farmiga), will still engage with him, but she’s responsible for getting Earl together with a scout for a drug cartel.

Soon Earl is driving to El Paso to deliver packages to the Midwest. His age and clean driving record make him the perfect mule. Earl may be unaware at first of what he is transporting, or he may just be acting old to protect himself. But once he gets his house back, and buys a new, tricked-out pickup, he can’t pretend he isn’t profiting from drugs.

For a story this dark and morally complicated, Eastwood adopts a sunny, casual tone. There’s plenty of time for vistas to unfold, for visits to roadside eateries, for glimpses of small-town life. Scenes in suburban motels and VFW bars are as authentic as the musical choices (right down to Mollie B’s cameo).

The Mule doesn’t avoid the consequences Earl must ultimately face. But Eastwood the director takes the time to figure out the drug dealers, just as Earl’s character figures out how to deal with them. A subplot about DEA agents is handled briskly, even superficially, but it gives Eastwood a chance to share the screen with his American Sniper star Bradley Cooper.

The Mule doesn’t avoid the consequences Earl must ultimately face. But Eastwood the director takes the time to figure out the drug dealers, just as Earl’s character figures out how to deal with them. A subplot about DEA agents is handled briskly, even superficially, but it gives Eastwood a chance to share the screen with his American Sniper star Bradley Cooper.

Precise and formal, Eastwood is also a playful filmmaker who loves to provoke. Critics who call Earl Stone a problematic and racist character simply aren’t paying attention. Earl may use the term “Negro,” but he treats a black family in need as equals. He uses slurs like “beaner,” but Eastwood stops The Mule for a perfectly staged, remarkably tense roadside encounter between a half-dozen cops and an innocent Latino driver fully aware that he could be shot at any moment. “Statistically speaking, this is the most dangerous five minutes of my life,” he says to the agents surrounding his truck.

It’s a moment that has nothing to do with plot (we never see the driver again). But it deals more honestly with society and culture than anything in the lightweight, softheaded The Old Man & the Gun.

Critics will misread the movie because of Eastwood’s politics, just as they misread American Sniper, Gran Torino, and Eastwood movies all the way back to Dirty Harry. Walt Kowalski in Gran Torino may spout racist comments, but he is the only one in the movie to accept his Hmong neighbors as equals. As for the supposedly gung-ho, politically reactionary American Sniper, patriotism steals Chris Kyle’s morals, beliefs, family, and ultimately his life.

How culpable is Earl Stone? Neither the screenplay nor Eastwood’s performance will say. But it’s hard not to read into the filmmaker’s own life when Earl expresses regret for the way he treated his family. Shot in silhouette as Cooper’s character watches, he admits, “I ain’t done much right in my life.”

It is a remarkable moment, both poignant and universal, and it’s presented in an unadorned manner that leaves Eastwood the performer completely exposed. Choices like that are why he remains one of cinema’s greatest living filmmakers.