The Toddle House was a small diner off the main drag in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, a block or two either way from the train station and the bus terminal. Open all night, it was the only place within miles for coffee and cheeseburgers after all the fast-food joints had closed. It was not for kids, which made it all the more appealing to us kids making our first tentative steps to adulthood.

Inside: harsh fluorescent lighting, white-tiled walls, a counter with swivel stools, a grille that sizzled and clanged. Plastic glasses, worn-out silverware, thick ceramic cups and plates. Soups, hamburgers, sandwiches, milk shakes, deserts, not much more. Smoke from the grille, but also from the customers and the waitress, clouds hanging heavy in the white glare.

Trying to fit in, we bantered with the staff, lit Marlboros with our coffee, punched each other on the shoulder. We’d put quarters in the jukebox, choosing musicians meant to reassure the older customers that we were okay. Tony Bennett, Roy Orbison, Tammy Wynette, nothing too rock or R&B.

We played country songs like “Take This Job and Shove It” or “The Lord Knows I’m Drinking,” choices we thought were dripping with irony, but were really just efforts to not look like jerky kids. My friends often picked Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee,” its lyrics drowned out in the hubbub, all except that annoying line in the chorus, “I’m proud to be an Okie from Muskogee.”

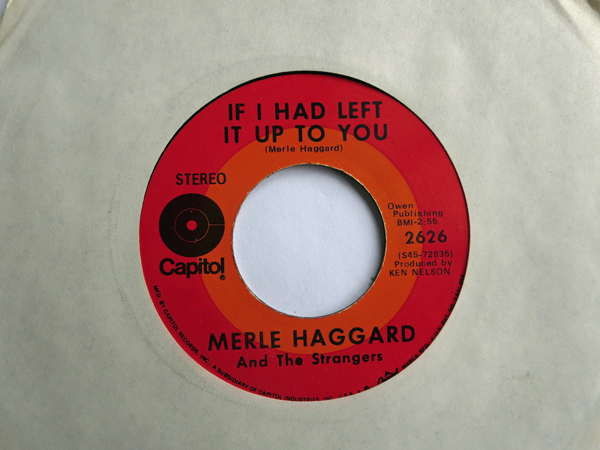

Maybe by mistake, maybe just to avoid hearing “Okie” once again, I played the other side, “If I Had Left It Up to You.” And maybe not the first time I heard it, or the second, but at some point in that diner country music started to make sense to me.

“If I Had Left It Up to You” was a moody, downbeat number, something to slow dance to, or to sit at a bar fingering a shot glass. Like many of Haggard’s ballads at the time, you could hear the strong influence of Buck Owens singing “Crying Time” or “Together Again.” I couldn’t recognize the Bakersfield sound yet, but it was there, in the minimal backing band, the voice up front in the mix, the electric guitarist bending his notes, the weeping steel guitar in the chorus.

Merle’s honeyed croon, deep, mournful, world-weary, cut through the din of the diner, made me forget the food I was eating, the earlier night, the day ahead. What struck me most were his words, knowing, fatalistic, a passive-aggressive plea to someone already departed.

“If I had left it up to you, it would all be over now. It’d all be over now, except the crying.”

That subjunctive mood absolves the singer of wrongdoing, makes whatever he did abstract, and turns his relationship into a series of missed opportunities leading to failure. He doesn’t want it to end, but there’s nothing he can do to stop it. It’s not even his fault.

“I wish I had found a way to let you go somehow…”

But why did he want to let her go? Why did he want to cry?

The conundrum behind the lyrics, the song’s simple, understated setting, and Haggard’s rich, full voice: this was reason enough to love country music.

The conundrum behind the lyrics, the song’s simple, understated setting, and Haggard’s rich, full voice: this was reason enough to love country music.

I won’t say I embraced the genre. There were still too many patriotic rednecks, too many cornpone comics and square old-timers, too many fiddles and back-up singers.

But Haggard showed me a way to appreciate the genre. He helped introduce me to musicians like Bob Wills, Jimmie Rodgers, Lefty Frizzell. I learned about his guitarist Roy Nichols, and how he had worked with The Maddox Brothers and Rose. About Haggard’s session band in Los Angeles, which included at times James Burton, Glen Campbell, and Ralph Mooney.

And I learned about Haggard’s life, the death of his father, his trouble with the law, his failed marriages, skirmishes with drink and drugs, gambling problems. It was all there in his songs, spun out over fifty years.

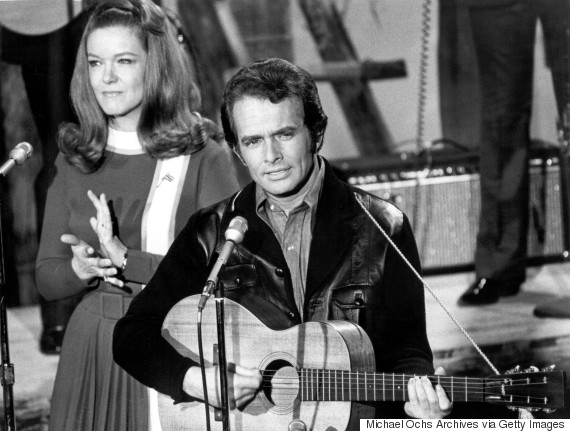

I still cherish my first Haggard concert, the late show at the tiny old Lone Star Cafe on 13th Street and 5th Avenue. The first show had been broadcast live over WSM; the second was supposed to start at 11:30. I sat upstairs, next to the balcony railing. The band ambled onto the stage hours late. And for what seemed like hours Merle picked his way through his catalogue and through the history of country music.

He was touring to promote The Way I Am, toward the end of his MCA contract, and drew liberally from his previous work. He dipped into his Capitol years, did some Wills and Emmet Miller, rocked hard through the fast ones and swung lazily through Jimmie Rodgers. I thought he nodded to Keith Richards, who sat at an adjoining table with his entourage, when he sang “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive”—”a fugitive must be a rolling stone.”

Merle was there through my most miserable breakup. His album The Way I Am closes with three Ernest Tubb songs and a Floyd Tillman chestnut. “Take Me Back and Try Me One More Time,” “I’ll Always Be Glad to Take You Back,” “It Makes No Difference Now,” “It’s Been So Long Darlin'” — “please don’t blame me if I cry.” The settings so pure, so gentle, Merle’s voice so knowing, so accepting as he charts the end of another affair. I felt if only I could express myself that way, if only my girlfriend could hear Merle singing, we would get back together.

I heard him on the radio driving south through the San Fernando Valley, where hits like “It’s Not Love (But It’s Not Bad)” and “Red Bandana” suddenly became California songs. I loved his live albums, his concept albums, I even made excuses for the rejects and outtakes his record labels would release, the discounts and cut-outs, his tribute to Elvis. I read his books, saw him in movies, tried but failed to keep up with him on TV. I followed his band members, mourned the loss of Bonnie Owens, put up with other singers interpreting his songs.

I saw him play in the round at the Westbury Music Fair, a dismal concert in a dispiriting setting. At the second Tramps on 20th Street, where he sang “White Line Fever” solo because the band didn’t remember it. At Studio 54, where the crowd insisted on an encore even after roadies dismantled the stage. At Radio City with Willie Nelson and Ray Price, before lung cancer sidelined him.

I even got to meet him, once in a green room at Madison Square Garden, where he was fourth-billed to Alabama for some cigarette-sponsored concert tour. He grinned and shook my hands for a picture, his eyes miles away.

Merle Haggard was one of the few constants in my life, one of the few artists I respected even when I disagreed with him—which was often. He made his life hard, but he found a way for himself. He left an enormous legacy.